思无邪,事以成

- 精诚所至,金石为开

前言

中国是一个不论从纵向的历史深度还是横向的生活广度上,都不轻浅的国家。生活在这片土地上的人,不论是经过几千年,或是经过近一个世纪全面现代化的进程,都仍然会抱有一种朴实的态度——如何“与祖辈的土地一起活下去”,是中国人精神的根。

这让我们始终保持了一种与西方世界截然不同的社会体系,也使得“时尚”这件事物,在中国的呈现形态,变得几乎无法以西方的思维方式来阐明。其实,不管我们是以东方的或是西方的思维方式探寻时尚,它本身并不依存于任何文化背景,时尚是人类欲望的反射,而欲望永存于每一个人。我想以一个热爱中国这片土地的年轻人的视角,以有别于西方的思考逻辑,借由这次展览,去尝试探讨时尚与人之间最纯粹的关系,探讨时尚本身应有却易被人们所忽略的普世价值。

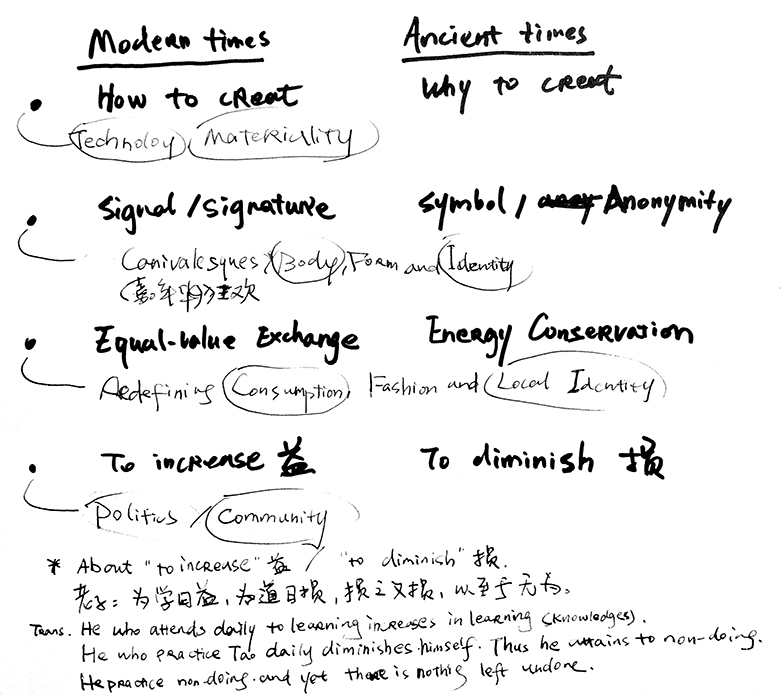

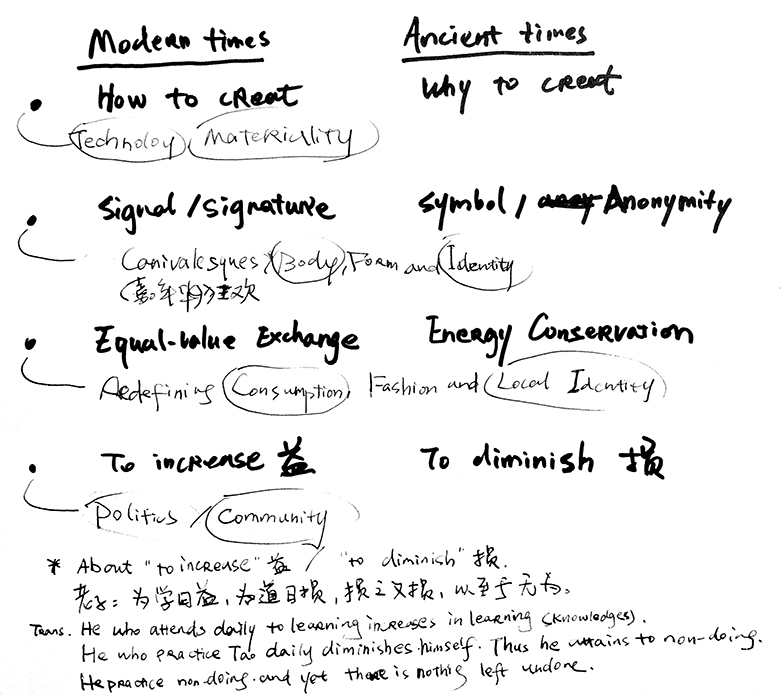

The Future of Fashion is Now 展览创作关键词 / 框架

1. 技术和材料如何影响设计

如何去做-为何而做

2. 服装的身份认同

个性(署名性)- 共性(匿名性)

3. 重新定义消费、时尚产业、本土设计

等价交换-能量守恒

4. 设计对社会/政治的影响

*益-损

*为学日益,为道日损,损之又损,以至于无为。——老子《道德经》第四十八章

正文

“我在乎的是人为何而动,而不是如何动。” 皮娜・鲍什 (德国现代舞编导家)

日益革新的现代技术,在带来便利的同时也有可能带来新的灾难。有最清洁的能源之称的核电,每一次意外事故都给人类带来百年之殇。如果我们能在科技发展的进程中,多问询一句:为什么我们需要这些“新”东西?而不是想着如何去实现,是否我们反而能另辟蹊径,挖掘到真正新的事物?现代科技的确让我们的生活充满了更多刺激和“可能性”,但这不表明人们精神上会更加富有。如果以中国古人的思考方式来观现世之貌,我们现在取得的进步,反而是种退化。

从去年开始,我对服装材料的研究重心转向了原始的手工面料。比如夏布*,一种用苎麻织成的手工平纹布,它有着哪怕是最精密的现代化机器也无法达到的生动和精细,而熟练的工匠用手就可以将布织得软薄如蝉翼,因手里握着的是不能被复制生产的匠心。

(*中国盛产苎麻,但并不是所有的苎麻布都能被称做“夏布”,为了在制作过程中不破坏苎麻的纤维结构又能达到薄如羽的效果,织造夏布需要极精细的手工劳作。在工业化批量生产盛行的现代社会,手工艺与人的关系不再似从前那般,也只有极少数的地方还能生产真正的夏布。)

概念系列 - 罅隙;消化设计工作间;2013

“这次的概念系列用了一种“粗暴”的方式,将几千颗金属四方螺母,分别穿入夏布纱线中,同样的三件夏布长袍,由于螺母的重量,呈现出了完全不同的轮廓,几十公斤重的衣服亦改变了人体本来的姿态。“粗暴”,不仅仅是形容现代机器时代对古典人文时代的颠覆,也描述了近代人类对待自己共生之地的行径。布料不堪重负的样子,让我难过;而被拉扯的身体,仿佛残喘于工业文明罅隙里的原生文明,丧失了天然之姿。图:中间夏布长袍穿入了2000颗方型螺母,约十公斤重;右侧长袍穿入4000颗,约二十公斤重。”

万物生生,而变化无穷焉。——周敦颐,太极图说。

是以思无邪,事以成。

*《万物:中国艺术中的模件化和规模化生产》选段,中国人对于“重复”的态度:

复制是大自然赖以生产有机物体的方法。没有什么东西能够被凭空创造出来。每一个个体都稳固地排列在其原型与后继者旳无尽序列之中。声称以造化为师的中国人,向来不以通过复制进行生产为耻。他们并不像西方人那样,以绝对的眼光看待原物与复制品之间的差异。如此的一种态度在其跨入克隆软件之时或许令人烦扰,但其也曾导入人类最伟大的发明之一:印刷术。在西方的价值体系中,艺术中的复制历来具有轻蔑的含义。在本世纪,瓦尔特.本雅明(Walter Benjamin)的观点具有指导性且影响深远,他公然宣称:一件艺术作品,倘以技术手段加以复制,就会丧失其风采神韵。然而,最近的研究发现,在欧洲中世纪艺术中,复制确实被用作界定艺术传统乃至加强特定作品感染力的手段。

中国浩瀚宏富的理论著述,均论及有关创造力的问题,尤其对视觉艺术中的创造性关注更多。始终如一,人类的创造力总是被描述在与自然造——被奉为最高的范本¬¬——的关系之中。我们被告知,古圣先贤在凝视着玄鸟的足迹时发明出了文字。早期的论文描述书法的品格大都借用自然意象:譬如将其喻为和风从竹林吹拂而过或凤凰翔于云彩之中。赞扬一位艺术家捕捉生活现象就像大自然所为,是中国的评论家所能给予的最高赞誉。

在西方的传统中,艺术家业以效法自然为第一要义,但是他们追求目标的途径却迥然不同。从两位希腊画家比试何者的画作更容易使观众误以为真之时起,现实主义的问题、逼真与模仿的问题就激励并困扰西方的画家直至今日!

对中国的艺术家来说,模仿并不具有至高无上的价值(只有在为死者作肖像时他们才力求逼真)。与其制作貌似自然造物的作品,他们更想尝试依照自然地法则进行创造。这些法则包括了大量有机进行创造。这些法则包括了大量有机体的不可思议之创造。变异、突变、变化,随时随处不断增加,终于形成全新的形态。

看起来,西方人好奇的传统根深蒂固,热衷于指明突变与变化发生的所在。他们的意图似乎在于学会缩短创造的过程并使之更加便捷。在艺术中,这种勃勃雄心可能造成一种结果,那就是习惯性地要求每一位艺术家及每一件作品都能标新立异。创造力被狭义地定向于革新。而另一方面,中国的艺术家们从未失去这样的眼光:大批量的制成作品也可以证实创造力。他们相信,正如在自然界一样,万物蕴藏玄机,变化将自其涌出。

摘自《万物:中国艺术中的模件化和规模化生产》6-7页,1998,雷侯德[德]

Pure hearts make truly new and infinite things

Theme1. The Influence of Technology and the Interest in Materiality

Top: The middle long robe made in summer cloth was sewn with 2000 square nuts, that measures approximately 10 kilograms, the long robe on the right was sewn with 4000 nuts, that measures 20 kilograms.” Text - Dooling Jiang Translation - Hooh Cheung post date: 2014/10/21

- Nothing is impossible for a faithful heart, faith moves mountains.

Preface

Before summarizing fashion the theme of the project, I’d like to state how Chinese people interpret clothing and fashion first. We cannot choose the birthplace we were born into thus the interpretation reflects our national characters indeed. Being a young Chinese designer my statement may represent the attitude of the young generation towards fashion and hope what I try to show you here would be effective. From aspects of accumulation of history and width of everyday life engagement, China has been known that has rich heritages in both. The people living on this land are strongly tied in with a faith of “to live together with our native land” (a core spirit). Thousands of years has gone through, the faith never dies though the tide of modernization pushing this nation to diverse terrifically in recent one hundred years. The remained unique social system results in a dilemma, fashion the term cannot be understood with the typical Western thinking model in China. However, fashion the phenomenon does exist no matter we explore it in what backgrounds, what makes fashion possible is desire. Fashion is an aggregation of a man’s desire; therefore, what I may contribute to the current fashion system is to uncover the purest relationship of men and fashion as well as to discuss the universal value of this relationship.

Structure & Key Words of The Future of Fashion is Now exhibition

How to creat - Why to creat

Theme2. Carnivalesque / Body, Form and Identity

Signal (signature) – Symbol (anonymity)

Theme3. Redefining Consumption, Fashion and Local Identity

Equivalent Exchange - Energy Conservation

Theme4. Politics / Community

* To increase (on purpose) - To diminish (on no purpose)

* He who attends daily to learning increases in learning. He who practices Tao daily diminishes himself. Thus he attains to non-doing. He practices non-doing and yet there is nothing left undone. - Chapter 48, Tao Te Ching, Laozi

Main Body

“I’m not interested in how people move, but what moves them.” - Pina Bausch (German performer of modern dance)

In modern age, the technological revolution will probably lead to disaster; for instance, nuclear power was considered the cleanest energy source but things do not turn out the way we wished; nuclear accidents bring us in pain and if we could have asked WHY do we need these new technologies in human history instead of just simply asked HOW do, we might have found another way more healthy and pure. Modern technologies do make human life more indulging and full of so-called “possibility”, but it does not necessarily mean our spirit becomes richer. We are in fact degraded when observing the society by the ancient Chinese philosophy (Tao).

My design work started from last year and the research of dealing with materials inevitably oriented the direction to primitive handmade fabrics, like Grass Cloth, the fabric with full craftsmanship made from ramie*. It is as thin as a cicada’s wings and as gentle as silk; even high-tech weaving machines cannot imitate because of the uncopiable ingenuity of mankind.

(*ramie is largely produced in China, yet not all ramie cloth may be called summer fabric, because true summer fabric requires rather complex weaving craftsmanship without damaging its natural fiber structure. Nowadays, there are very few places and individuals who can produce the true summer cloth, especially that the contemporaries no longer value the craftsmanship)

Artistic line Hua “Crack”, Digest Design Work-shop, 2013

“This conceptual line has adopted a “crude” approach that threaded thousands of metallic square nuts in the weaving of the summer fab-ric. The varying weight of the nuts have config-ured the three identical summer long robes into different forms, and the weight of the clothes has thus changed the inherent shapes of the human body. “Crude” is not only used to depict the subversion to the modern industrial era versus the classical civilization, but is also used to describe the path on which the contemporary inhabits. The fabric’s inability to bearing such responsibility saddens me; and the struggling body seems to be the primitive culture fallen into the cracks of the industrial civilization that has lost its intrinsic posture.

In ancient China, no such a profession of designer exists. Traditional Chinese module and mass production (inheriting from thousands of years ago) share a similar principle of modern mechanical scale-production. Who take over the procedure of the module production unlike today, are literati and craftsmen in ancient times and they devote their talents across areas like architecture, costume, appliance, painting etc. Most of those literati and craftsmen erase their names off from the scene; nobody knows who a particular person designed the Forbidden City. The reason of why they keep anonymous is they achieve the completion of their talents and values through associating, negotiating, and processing the whole procedure to a perfect finish. The faith of purely undertaking tasks and meeting expectations is the most different notion comparing to the modern belief of sign¬ing one’s signature around and promoting one’s self out loud.

Now back to fashion, fashion is always an honest reflection of human desire. Hu¬man desire can be boundless, but the world need not comply with it. The world is actually built up by real hand labour, thus the value of craftsmanship given by craftsmen and literati is the most precious by any means. Craftsmanship perfectly tells the truly “new” of man’s authentic objectiveness which could break through the emotionless mechanical production at present. Under this foundation, “new” is infinite. In this project, I will continue my work in this pathway to express the term that “new”.

“The ten thousand things are produced and reproduced, so that variation and transformation have no end.” - Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073) Diagram of the supreme ultimate explained

Pure hearts make truly new and infinite things.

*Below words is selected from 《Ten Thousand Things》, Chinese’s attitude towards repetition.

“Reproduction is the method by with nature produces organisms. None is created without precedent. Every unit is firmly anchored in an endless row of prototypes and successors. The Chinese, professing to take nature as their master, were never coy about producing through reproduction. They did not see the contrast between original and reproduction in such categorical terms as did westerners. Such an attitude may be annoying wen it comes to cloning software, but it also led to one of the greatest inventions of humankind: the technique of printing. In the western value system, reproduction in the arts has traditionally had a pejorative connotation. Indicative, and influential in our century, has been the view of Walter Benjamin, who declared that a work of art loses its aura when reproduced by technical means. However, recent research has un covered that in the arts of the European Middle Ages, for instance, reproduction could indeed be used as a means as define an artistic tradition, and even to reinforce the impact of specific works.

A rich and profuse body of theoretical writings in china deals with the issue of creativity, especially in the visual arts. Invariably. The creativity of humans is described in relation to the creativity of nature, which is upheld as the ultimate model. We are told that sage of antiquity invented script when gazing at the footprints of birds. Early treaties describe the qualities of calligraphy in terms of nature imagery such as a gentle breeze through a bamboo grove, or phoenix soaring to the clouds. Praising an artist for his “spontaneity”(ziran) and ”heavenly naturalness” (tianran). Or saying that he captured life as nature does, are the highest acclaim a Chinese critic can bestow.

Artists in the western tradition consider the emulation of nature a primary task, too, but they have been pursuing it on a different course. Beginning with the competition between two Greek painters to determine which of their paintings a viewer would more readily mistake as real, questions of realism, verisimilitude, and mimesis have stimulated and haunted western artists down to today.

To Chinese artists, mimesis was no of paramount importance. (Only in images of the dead did they strive for verisimilitude.) Rather than making things that looked like creations of nature, the tried to create along the principles of nature. These principles included prodigious creations of large numbers of organisms. Variations, mutations, changes here and there add up over time, eventually resulting in entirely new shapes.

There seems to be a well-established western tradition of curiosity, to put the finger on those points where mutations and changes occur. The intention seems to be to learn how to abbreviate the process of creation and accelerate it. In the arts, this ambition can result in a habitual demand for novelty form every artist and every work. Creativity is narrowed down to innovation. Chinese artist, on the other hand, never lose sight of the fact that producing works in large number exemplifies creativity, too. They trust that, as in nature, there always will be some among the ten thousand things from which change springs.”

(Page6-7, The Thousand Things-Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art, 1998, Lothar Ledderose)